View libraries and data used in these notes

library(tidyverse)

library(tidymodels)

orings = read_csv("https://sta221-fa25.github.io/data/orings.csv")Dr. Alexander Fisher

In January 1986, the space shuttle Challenger exploded 73 seconds after launch.

The culprit is the O-ring seals in the rocket boosters. At lower temperatures, rubber becomes more brittle and is a less effective sealant. At the time of the launch, the temperature was 31°F.

Could the failure of the O-rings have been predicted?

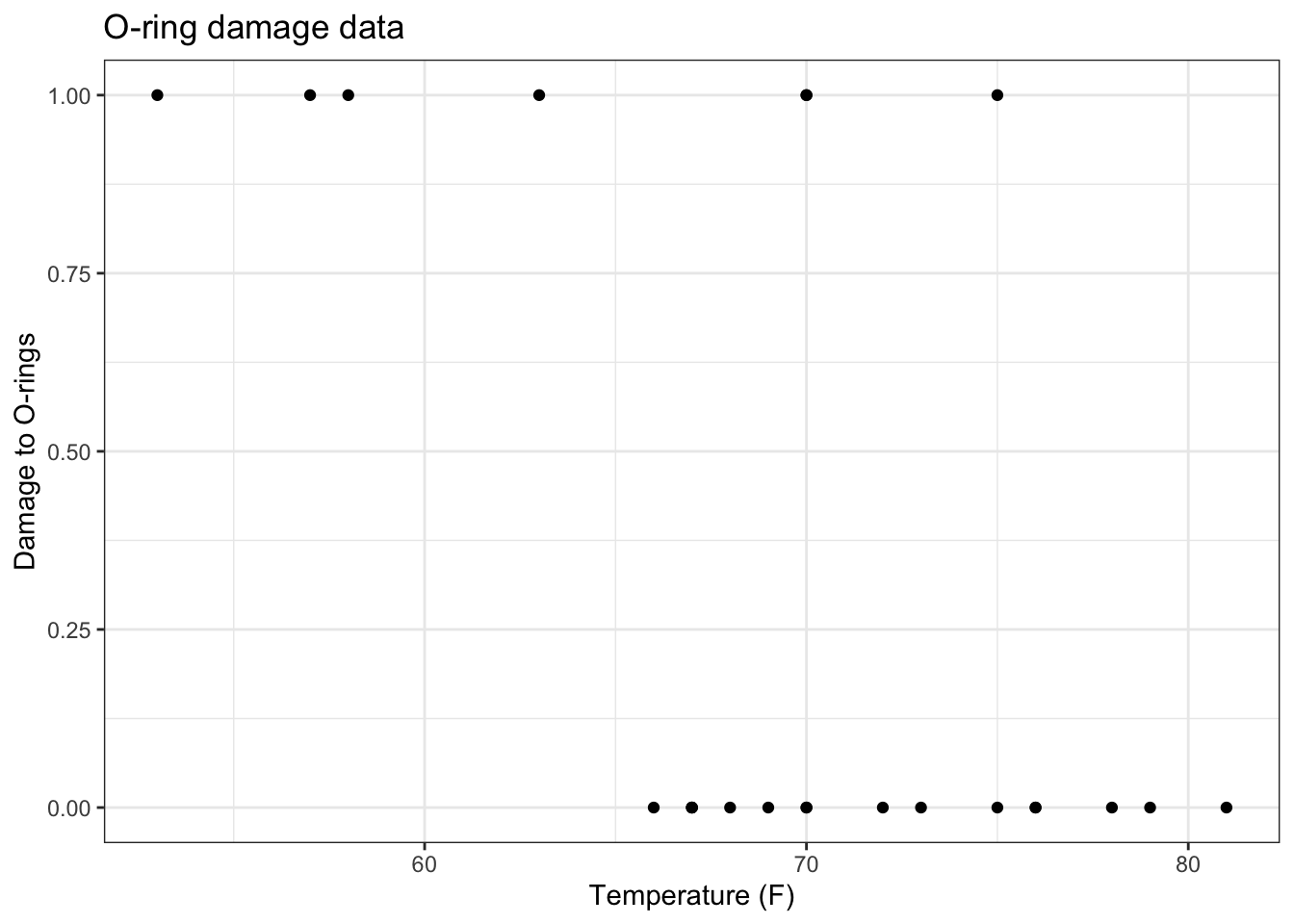

Data: 23 previous shuttle missions. Each shuttle had 2 boosters, each with 3 O-rings. We know whether or not at least one of the O-rings was damaged and the launch temperature.

# A tibble: 23 × 3

mission temp damage

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 1 53 1

2 2 57 1

3 3 58 1

4 4 63 1

5 5 66 0

6 6 67 0

7 7 67 0

8 8 67 0

9 9 68 0

10 10 69 0

11 11 70 1

12 12 70 0

13 13 70 1

14 14 70 0

15 15 72 0

16 16 73 0

17 17 75 0

18 18 75 1

19 19 76 0

20 20 76 0

21 21 78 0

22 22 79 0

23 23 81 0Notice any patterns?

orings %>%

mutate(failrate = damage) %>%

ggplot(mapping = aes(x = temp, y = failrate)) +

geom_point() +

labs(x = "Temperature (F)", y = "Damage to O-rings", title = "O-ring damage data") +

theme_bw()

\[ \begin{aligned} Prob(Y_i = 1) &= p\\ Prob(Y_i = 0) &= (1-p) \end{aligned} \]

What is \(E[Y_i|p]\)?

\[ \begin{aligned} E[Y_i|p] &= \sum_{Y_i = 0}^1 Y_i \cdot prob(Y_i)\\ &= 0 \cdot prob(Y_i = 0) + 1 \cdot prob(Y_i = 1)\\ &= 0 \cdot (1-p) + 1 \cdot p\\ &= p \end{aligned} \]

In linear regression, we are concerned with modeling the conditional expectation of the outcome variable. (Previously: \(E[y|X] = X\beta\)).

Here, the conditional expectation \(E[Y_i | p] = p\).

If \(p = 0.5\), what does the statemeny \(E[Y_i | p] = p\) say, in terms of the data at hand? Is this assumption realistic?

That the probability of O-ring failure is 0.5 for all observations.

Not realistic given EDA above.

We want to have individual observation probabilities \(p_i\) that depends on the covariate temperature.

What’s wrong with letting \(p_i = x_i \beta\)?

\(p_i\) is bounded between \([0, 1]\), \(x_i \beta\) is not. See figure above again.

Remedy: let

\[ \text{logit}(p_i) = x_i^T\beta \]

where \(\text{logit}(p_i) = \log \frac{p_i}{1-p_i}\). Since the logit function links our conditional expectation to the predictor(s), we call the logit function a link function.

What happens as \(p_i \rightarrow 0\)?

What happens as \(p_i \rightarrow 1\)?

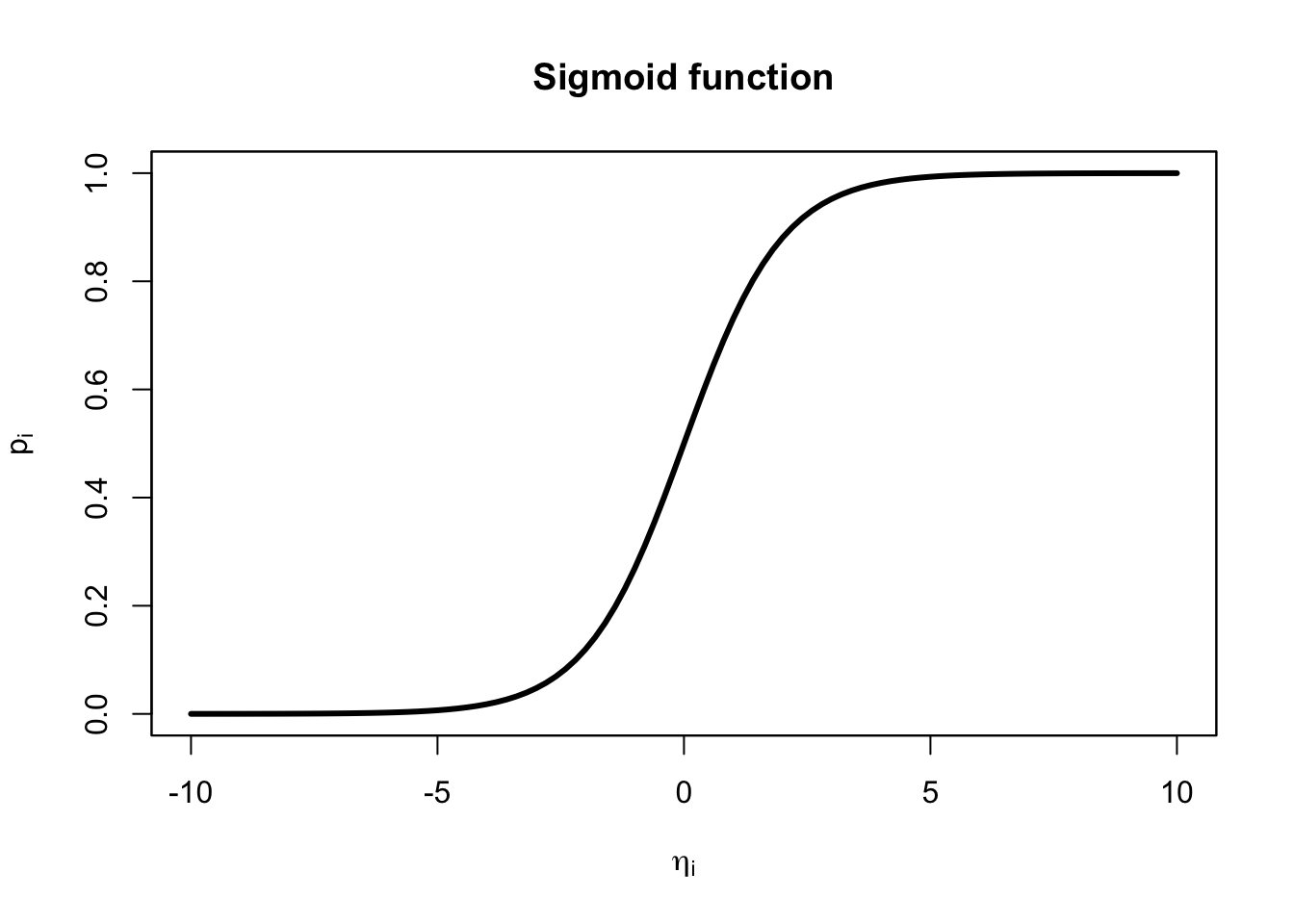

\[ p_i = \frac{e^{\eta_i}}{1 + e^{\eta_i}} = \frac{1}{e^{-\eta_i}+ 1}, \]

where the second equality comes from multiplying by 1 in a fancy way: \(\frac{e^{-\eta_i}}{e^{-\eta_i}}\) and \(\eta_i = x_i^T\beta = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_1 + \ldots\) is called the linear predictor or systematic component.

\[ \eta_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_{i1} + \cdots + \beta_{q} x_{iq} = \mathbf{x}_i^T \boldsymbol{\beta} \] The function \(p_i = \frac{e^{\eta_i}}{1 + e^{\eta_i}}\) has a special name. It is called a “sigmoid” function. Let’s take a look at the sigmoid function:

Here’s our model:

\[ E[Y_i | X] = p_i = \frac{1}{e^{-x_i^T\beta}+ 1} \]

The likelihood of the data is the joint density of the data, viewed as a function of the unknown parameters:

\[ \begin{aligned} \underbrace{p(y_1, \ldots, y_n| X, \beta)}_{\text{joint density of data}} &= \prod_{i=1}^n p(y_i|X, \beta)\\ &= \prod_{i=1}^np_i^{y_i} (1-p_i)^{1-y_i} \end{aligned} \]

Practically, we want to examine the log-likelihood for numerical stability. Recall: maximizing the log-likelihood (finding \(\hat{\beta}_{MLE}\)) will be the same as maximizing the likelihood since \(\log()\) is a monotonic function.

\[ \begin{aligned} \log p(y_1, \ldots, y_n | X,\beta) &= \sum_{i=1}^n y_i \log(p_i) + (1-y_i) \log(1 - p_i) \end{aligned} \] Plugging in \(p_i\), we view the log-likelihood as a function of the unknown parameter vector \(\beta\), and we can simplify:

\[ \begin{aligned} \log L(\beta) &= \sum_{i=1}^n y_i \log \left(\frac{e^{x_i^T\beta}}{1 + e^{x_i^T\beta}} \right) + (1-y_i) \log \left(\frac{1}{1 + e^{x_i^T\beta}} \right)\\ &= \sum_{i=1}^n y_i x_i^T \beta - \sum_{i=1}^n \log(1+ \exp\{x_i^T \beta\}) \end{aligned} \]

\[ \begin{aligned} \frac{\partial \log L}{\partial \boldsymbol\beta} =\sum_{i=1}^n y_i x_i^\top &- \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{\exp\{x_i^\top \boldsymbol\beta\} x_i^\top}{1+\exp\{x_i^\top \boldsymbol\beta\}} \end{aligned} \]

If we set this to zero, there is no closed form solution.

R uses numerical approximation to find the MLE.

Call:

glm(formula = damage ~ temp, family = "binomial", data = orings)

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

(Intercept) 15.0429 7.3786 2.039 0.0415 *

temp -0.2322 0.1082 -2.145 0.0320 *

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

(Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

Null deviance: 28.267 on 22 degrees of freedom

Residual deviance: 20.315 on 21 degrees of freedom

AIC: 24.315

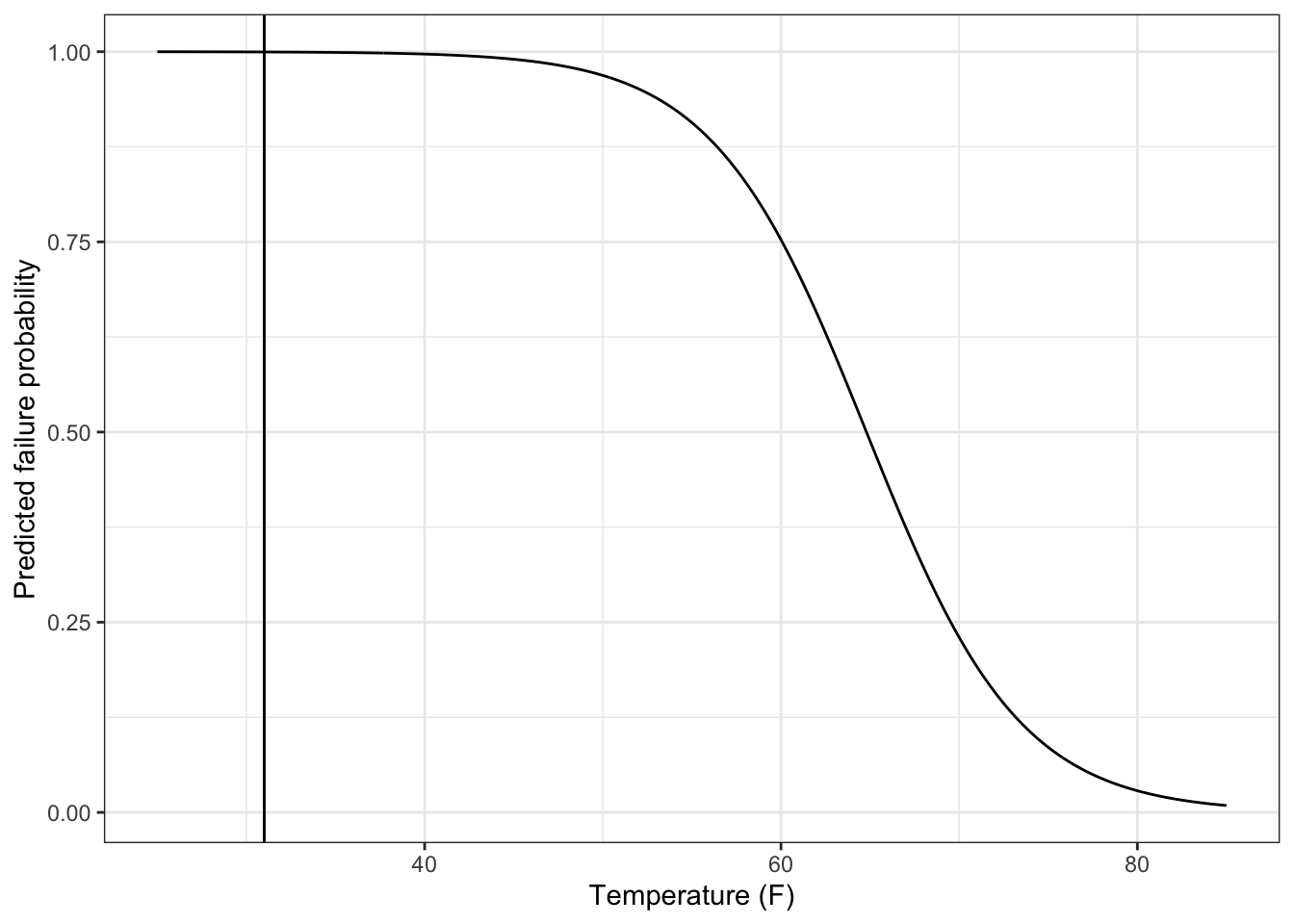

Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 5Now we can predict the failure probability. The failure probability at 31F is nearly 1.

test_31F = tibble(temp = seq(25, 85, 0.1),

predprob = predict(orings_fit, newdata = tibble(temp = temp), type = "response"))

test_31F %>%

ggplot() +

geom_line(mapping = aes(x = temp, y = predprob)) +

geom_vline(xintercept = 31) +

labs(x = "Temperature (F)", y = "Predicted failure probability") +

theme_bw()

# make augmented model fit

orings_aug =

augment(orings_fit)

# add to the augmented model fit a column for

# predicted probability

orings_aug$predicted_prob =

predict.glm(orings_fit, orings, type = "response")

orings_aug %>%

mutate(y = damage) %>%

select(predicted_prob, .fitted, y) %>%

head(5)# A tibble: 5 × 3

predicted_prob .fitted y

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 0.939 2.74 1

2 0.859 1.81 1

3 0.829 1.58 1

4 0.603 0.417 1

5 0.430 -0.280 0predicted_prob: predicted probability that \(Y_i = 1\), i.e. \(\hat{p}_i\).fitted: predicted log-odds, i.e. \(\log \left(\frac{\hat{p_i}}{1 - \hat{p}_i}\right)\).y: actual outcomeThanks to Prof. Hua Zhou for example.