View libraries and data sets used in these notes

library(tidyverse)

library(tidymodels)

library(DT)

library(latex2exp)

library(patchwork)

pokemon <- read_csv("https://sta221-fa25.github.io/data/pokemon_data.csv") # complete, population dataDr. Alexander Fisher

As of 2025, there are 1025 pokemon in existence.

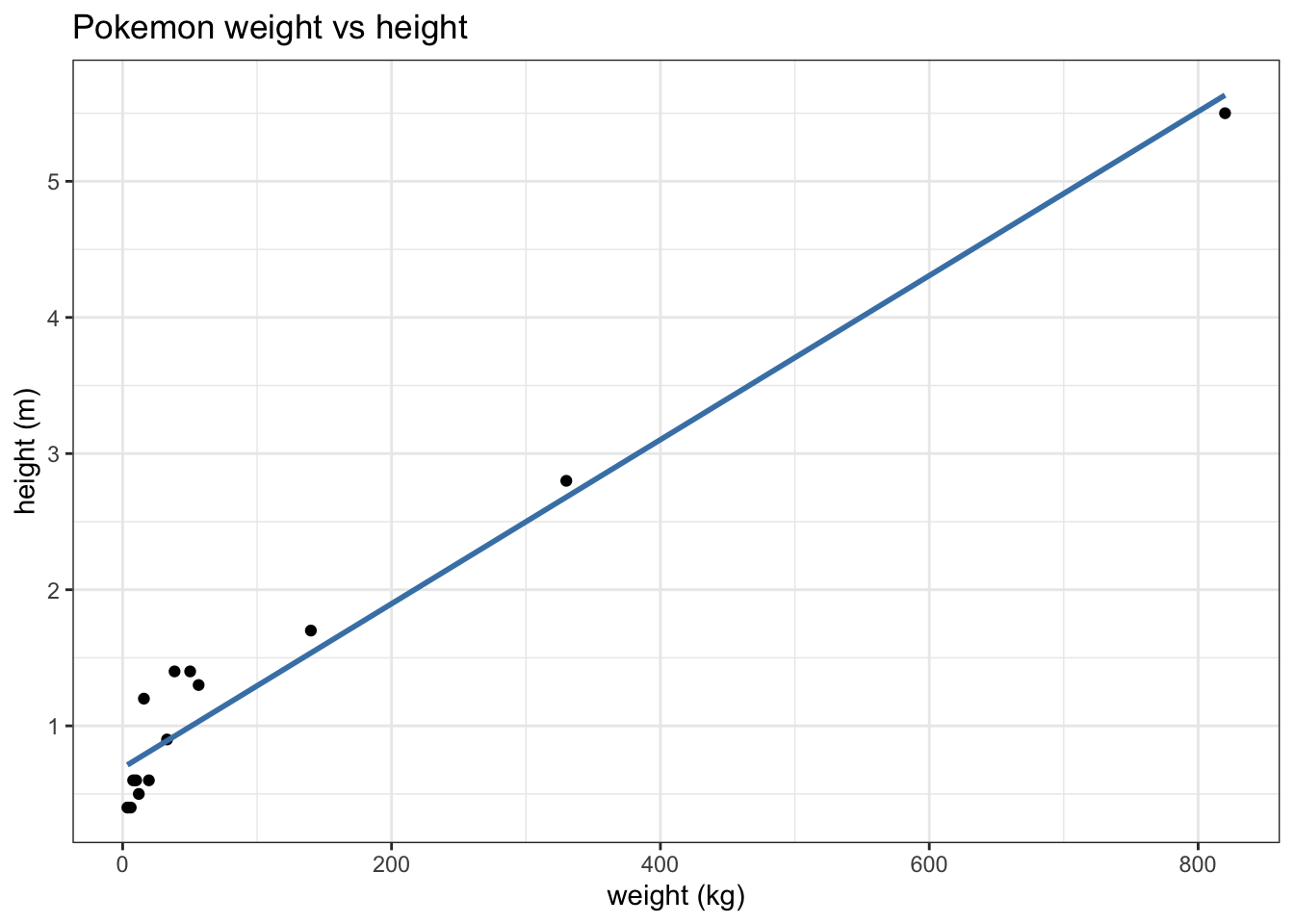

In all statistical inference tasks, we only have a sample from the population. Let’s consider a random sample of the pokemon data, given below:

set.seed(48)

pokemon_sample <- pokemon |>

slice_sample(n = 15) |>

select(dexnum, name, height_m, weight_kg) |>

arrange(dexnum)

datatable(pokemon_sample, rownames = FALSE, options = list(pageLength = 5),

caption = "sample of 15 pokemon")Let’s investigate the question: are heavier pokemon taller?

How can we tell if our estimates \(\hat{\beta}\) are any good?

pokemon_hw = pokemon |>

select(height_m, weight_kg)

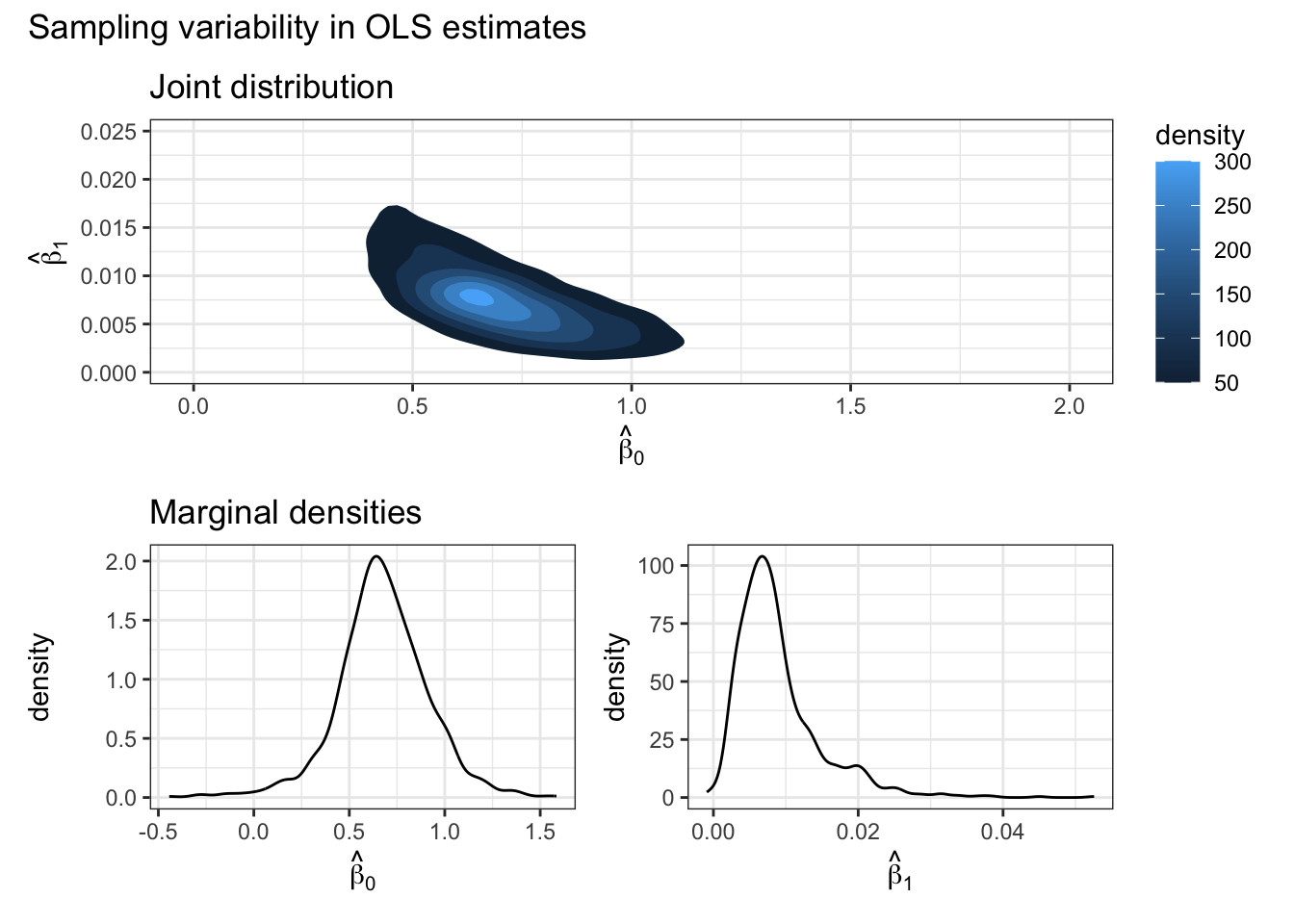

BETA_HAT <- NULL

for(i in 1:1000) {

fit <- pokemon_hw |>

slice_sample(n = 15) |>

lm(height_m ~ weight_kg, data = _)

BETA_HAT <- rbind(BETA_HAT, fit$coefficients)

}

BETA_HAT <- data.frame(BETA_HAT)

colnames(BETA_HAT) <- c("beta0", "beta1")

glimpse(BETA_HAT)Rows: 1,000

Columns: 2

$ beta0 <dbl> 0.9016025, 0.5209848, 0.6775509, 0.8639395, 0.4678607, 0.4351285…

$ beta1 <dbl> 0.004823824, 0.010159875, 0.008377374, 0.012071556, 0.016425420,…

Our objective is to infer properties about a population using data from an experiment or survey (in this case, a survey/sample of pokemon).

Post-experiment: after collecting the data, \(\hat{\beta}_0, \hat{\beta}_1\) are fixed and known.

Pre-experiment: before collecting the data, the data are unknown and random. \(\hat{\beta}_0, \hat{\beta}_1\), which are functions of the data, are also unknown and random.

In all cases, the true population parameters, \(\beta_0, \beta_1\) are fixed but unknown.

Pre-experimental question: is the probability distribution of \(\hat{\beta}_0, \hat{\beta}_1\) a meaningful representation of the population?

Answer: this depends on certain assumptions we make about population.

\(E[\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}|\boldsymbol{x}] = \boldsymbol{0}\), or equivalently, \(E[\varepsilon_i|\boldsymbol{x}] = 0\) for all \(i\).

Implications: in simple linear regression, assumption 1 implies that \(E[y_i|\boldsymbol{x}] = E[\beta_0 + \beta_1 x_i + \epsilon_i|\boldsymbol{x}] = E[\beta_0 |\boldsymbol{x}] + E[\beta_1 x_i|\boldsymbol{x}] + E[\epsilon_i|\boldsymbol{x}] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_i\).

Show that assumption 1 implies that \(E[\hat{\beta}|\boldsymbol{X}] = \beta\).

\[ \begin{aligned} E[\hat{\beta}|\boldsymbol{X}] &= E[(\boldsymbol{X}^T\boldsymbol{X})^{-1}\boldsymbol{X}^T\boldsymbol{y}| \boldsymbol{X}]\\ &= (\boldsymbol{X}^T\boldsymbol{X})^{-1}\boldsymbol{X}^T E[\boldsymbol{y}| \boldsymbol{X}]\\ &= (\boldsymbol{X}^T\boldsymbol{X})^{-1}\boldsymbol{X}^T \boldsymbol{X}\beta\\ &= \beta \end{aligned} \]

Since \(E[\hat{\beta}|\boldsymbol{X}] = \beta\), we say \(\hat{\beta}\) is an unbiased estimator of \(\beta\).

Notice that this result (unbiasedness) does not depend independence of errors, normality, or constant variance.

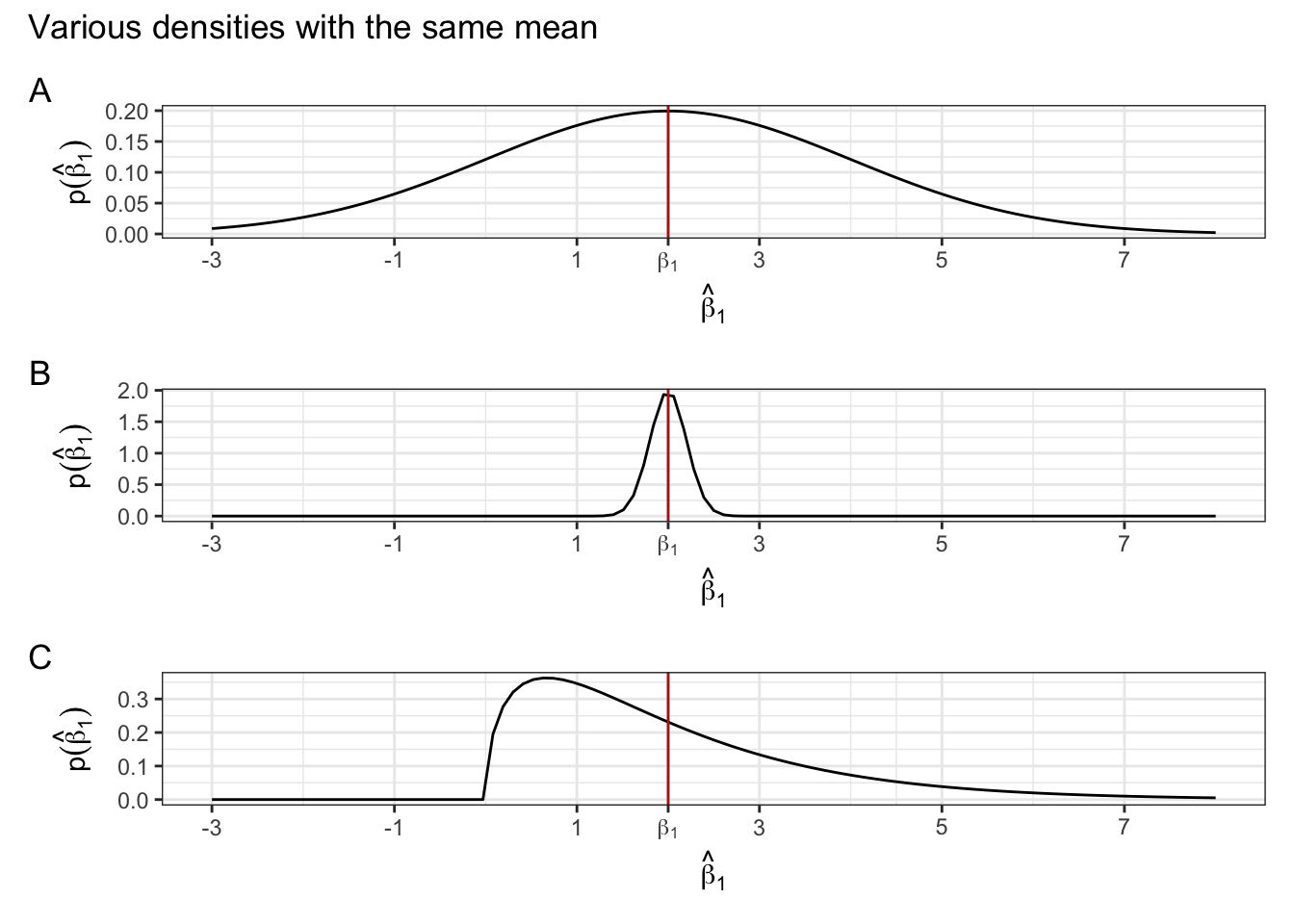

However, the result doesn’t tell us anything about how close \(\hat{\beta}\) will be to \(\beta\). The estimator may be unbiased, but by itself, this doesn’t tell us much. See examples of “unbiased” distributions of an estimator below.